Goldilocks and the Three Bundles

As children, the concept of “free choice” is introduced to us quite early, in the form of the classic folk fairy tale “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.” Yet, the simplicity of those “big,” “medium” and “small” choices belies the complexity behind the video viewing pastime enjoyed by most Americans 5-6 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Tackling that complexity, The Wall Street Journal’s Joe Flint wrote a remarkable study, dated June 8, that captured the essence of that paradox known as the “American Pay TV Bundle.” His article presented a rare description by big media of the dilemmas facing today’s video distributors, content rights holders, viewers and a lot of others inside the U.S. video ecosystem. The possible solutions to that bundle dilemma are no doubt fodder for a future WSJ story.

To assist that effort, I wish to address a similar concern: Is a la carte a fairy-tale answer to America’s pay TV bundle?

I would posit this answer: Yes, it is.

But, meanwhile, we are certainly headed toward many more ”medium-sized” bundles, of every imaginable form and iteration.

The Push to A La Carte

Four main reasons support today’s idea that the pay TV marketplace is headed quickly toward a pure a la carte motif where everyone chooses and pays for only what they want (on a single-show or single-channel basis, or both).

The first reason is based on a cultural phenomena that is quintessentially American, called “free choice.” Our very society and economics are so often grounded in the theory, indeed, the hope, at least, of having the right to free choice when it comes to goods and services. Indeed, if a consumer can go into a grocery store and purchase single items on a list of 12, without the purchase of one item restricting the purchase of another, then why not also in today’s cable, satellite and telco pay TV services? Why, in order to get my pure choice of 17 channels should I have to buy a package with 133 other channels of no interest to me? That’s weird, right?

The second reason supporting a la carte is the unraveling of the traditional Multichannel Video Program Distributor (MVPD) model. Year-over-year increases in Tier 1 content costs are clobbering operator margins and driving subscribers away.

Third is the steady and dramatic increase in the quality and quantity of video distributed over the Internet. This phenomenon gives pay TV subscribers an additional reason to defect to the so-called Over-The-Top (OTT)/broadband/streaming distribution infrastructure.

The final reason supporting a la carte, specifically (and arguably a smaller part of the third reason above), is the resultant decrease in the viewing of live, linear, “appointment television.” This loss is replaced by a dramatic increase in the viewing of on-demand content and the accompanying changes in behavioral viewing patterns. Indeed, “binge viewing” is but one example of the new dynamics that support the idea of singular-choice TV.

The Myth of A La Carte

Yet, in that endless momentum toward a business and marketplace equilibrium, there are even more reasons on the side of an equally important question, i.e., Why are a la carte channels and programs also challenged? These, I also posit, are today stronger than those above that support the notion of pure a la carte.

These half dozen reasons are positioned below as “realities,” because these are examples of the real world shining light on a rather idealistic and visionary world that is today’s a la carte. Indeed, this is where Goldilocks’s lofty dreams and visions of simple choice and pure viewing freedom – indeed, her feet, and those of almost every other American video viewer -- are forced to meet the ground.

Personal Realities

Studies show that most U.S. TV viewers regularly covet and watch no more than 15-20 channels from among a typical U.S. mid-level pay TV package of 150-200 channels. The pure a la carte logic is that each viewer should be able to simply select those 17 or so channels, and like selecting 17 separate items in a grocery store, those (and only those separately) are what you pay for.

Unfortunately, for the pure a la carte pay TV notion, the video grocery store is much more complicated than a real grocery store.

In order to provide the most choice for the most people at the best overall prices, U.S. TV has created a forced system of subsidization, which clearly benefits content rights holders and distributors. Yet, it also appears to actually benefit the customer.

That is because by compelling everyone to subsidize other viewers’ channel choices, the selection remains quite large, and the subscription fee wealth is spread to many programs and channels, which otherwise would not be funded and thus not survive.

In this manner, you get your 17 channels pretty consistently. Meanwhile, I (and just about every other viewer) get mine (and they get theirs). In American pay TV today, that’s around 95 million sets of 17 channels.

Furthermore, most people do not want to add yet another set of video viewing decisions to their list of concerns; call that laziness or “other priorities,” if you will. That lack of passion to actually seek out my favorite 17, as a personal matter, also gets in the way of instant a la carte. For many, to get the channels I want – regardless of that other “channels I don’t want” nonsense – is what counts, and thus most just get used to (and accept) paying that overage.

This, then, is major reality # 1 of today’s big bundle vs. a la carte war.

Legal Realities

The “legal realities” backing bundles is a big – and important -- one.

That is because just as we are a country of strong choice, we are also a country of strong laws (which often trump strong choice).

The length of the licensing term for most major program agreements today is typically five years. That is because programmers and their distributors want to make longer-term business decisions, as a form of good business practices.

Another legal reality involves programmers adding terms that require several of their programs and channels to be purchased and shown as a group. This also is seen as a good business practice.

A third legal reality is the restriction from Internet and other IP-based distribution involving the top tier, most popular, programming. Arguably, the basis for this in the past was insecurity as to the copyright protection and thus payments receivable via IP, much of which is now past tense. That said, it still exists.

In the end, outmoded attitudes die hard, and antiquated contract restrictions die harder. This is particularly the case for licensing agreements that typically run those five-plus-year terms.

Yet, conversely, as the OTT/broadband/streaming market grows, the “old school” licensing deals will fall by the wayside. This includes changes in the top tier, linear, channels, as well.

Market Realities

Producing those top-quality television programs (or movies, or sporting events, or what have you) takes a lot of money.

Bloomberg View’s public policy, economics, finance, and business blogger, Megan McArdle, put this quite succinctly in her recent article “The Fault in John Green’s Cable Logic.” She pointedly observes: “You don't want your cable to be unbundled. You just want to pay less for it.”

So what happens when you unbundle? How much do you have to pay for your channels?

That's right: typically the same $150 as with pay TV. You aren't cross-subsidizing the channels you don't watch, but all those other people aren't cross-subsidizing all the channels they don't watch. So, you have to make up for that lost revenue if you are going to continue to pay for your favorite programs. Obviously, with fewer viewers to justify higher ad rates and subscription fees, that lost revenue has to be replaced in order to retain the shows and business models. That means higher subscription fees. The price for each channel goes up in the a la carte model, until you're paying about what you were before in your traditional bundle model.

According a not-so-recent-but-still-viable econometric study done by Harvard’s Dimitri Byazolov and printed by UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, households would save, on average, some thirty-five cents from their current monthly bills in that a la carte world.

Noteworthy is the fact that the 2008 Byazolov study cites a parallel 2008 theoretical study by Crawford and Yurukoglu that concludes unbundling substantially benefits consumers, however, the data, models, and assumptions are different enough to call it a wash. The point here seems to be that unless the “A La Carte Study” conclusion is clearly and consistently that consumers do better with a la carte, the industry is going to very likely continue supporting the bundled model.

Realizing this “market and business reality,” most consumers can more easily accept the 90% waste, 10% subsidization argument, and look for other ways to address video choice.

Thus, there is at least a valid argument that video cross-subsidization appears to work.

Economic Realities

Possibly the best way to define why the existing pay TV bundles work is to compare them to bundles offered by other industries.

In the hospitality world, for example, few, if any, hotels charge you by the towel, or bar of soap, or by the sheets for a multi-night stay. And fewer hotels now charge separately for wi-fi. Can you imagine a world where someone brings his/her own towel to avoid being charged separately for using those from the hotel? Sometimes the pure a la carte model doesn’t work.

The same holds true in the airline business, where most folks like me chafed greatly at the idea of paying separately for bags checked, use of the toilet, and even paying for access to food, entertainment, phone, Internet and food service.

Or in the car-buying world: one questions the ability to charge separately for tires, or gas caps, or bumpers, or in-dash systems. The American auto is a great comparison to the American pay TV bundle. Both support strong arguments that the bundle works (and will thus take a long time to significantly alter).

Plus, splitting things up often means much more effort and resources expended overall, because people have to be paid separately to do things and to purchase things separately, that make a la carte happen. This then adds an a la carte cost that then gets passed on to the consumer.

Business Realities

To put this in context, the global pay television market was about $269 billion in 2014 (ABI Research). Considered without context, OTT/broadband/streaming is doing gangbusters when you consider where it was five years ago. But OTT/broadband/steaming today doesn’t amount to 5% of the total pay television market. Thus, some moderation in the over-the-top hyperbole appears to be in order.

Stated another way, video providers today are unlikely to jettison big-to-medium-sized bundles that support traditional pay TV payments in big dollars, in place of OTT/broadband/streaming services that support payments in small pennies.

Viewing Realities

Perhaps one of the best measures of the current friction between traditional pay TV bundles and alternative OTT/broadband/streaming alternatives is Dish Network’s new Sling TV model. Some would say that it is good evidence of the weakness of traditional pay TV bundles.

But, most interestingly, the channels offered by Dish on Sling are not the same channels as those offered on the pay TV channels. Yet, per channel, consumers pay about the same for ESPN on Sling TV as they do on Dish. Nor can the SlingTV consumer buy only the five or ten or 17 channels that are his or her favorites. Is this then closer to the reality of a la carte – or merely an offer that satisfies the economic need to pay less?

Conclusions

The realities of the enormous business that is pay television make it practically impossible for each of us to realize our “a la carte” dream.

Until there is better proof that unbundling-toward-a-la-carte saves consumers real money, unbundling will proceed slowly and cautiously. Until businesses find viable business models that will hold up a la carte, they, too, will resist that change.

Conversely, there will be a few company breakaways, and rare contracts will be written that leave the established norms, during the next few years.

Indeed, we will get a lot closer to a la carte, but it will take many years. Instead, for now, at least, the logical conclusion is that most viewers will likely end up as Goldilocks did: choosing a bundle somewhere in the middle. This means a grouping of channels and shows not too big (like today’s bundles); not too small (like a la carte); but somewhere in the middle (like hundreds of new possible channels and shows, from old and new media, and a plethora of other new video combinations).

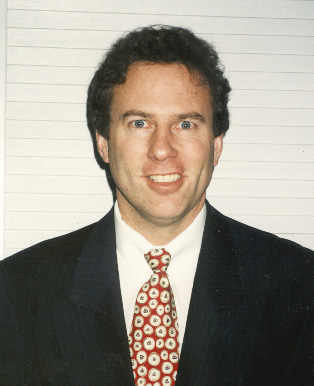

Jimmy Schaeffler writes about telecommunications and media. He is chairman and CSO ofconsulting firm The Carmel Group, Carmel-by-the-Sea, Calif.

Multichannel Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

Jimmy Schaeffler is chairman and CSO of The Carmel Group, a nearly three-decades-old west coast-based telecom and entertainment consultancy founded in 1995.