Peter Jennings' First Olympics: Lessons Learned In Munich

The 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, West Germany, was a landmark Olympics for many people in the world of television.

Because when the angst, pressure, and the stress of “getting the job done right,” reached never-before-known levels of professionalism, there were those in the Bavarian capital that year whose careers were made by what they did on that stage. Names like Arledge, McKay, Spence, Bader, Mason, Wilson, Jennett, and Goodrich come to mind; and careers were made by the Wilcoxes, Buffingtons, Goodmans, Fuchses, Browns, Katzes, McManuses, Peacocks, Gliddens, and the Ebersols of the TV world.

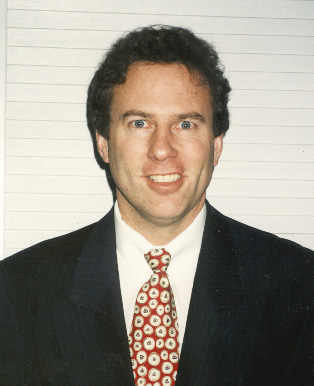

Another of ABC Munich’s top performers was a 34-year-old Canadian, with strong roots in Canadian broadcasting. That talent was Peter Jennings.

Peter Jennings had called ABC Sports’ executive producer, Roone Arledge, earlier in 1972, asking for a two-week leave of absence from ABC News, in order to join ABC Sports in August, as some kind of an on-air reporter at the Games. For several years before, Jennings had worked out of ABC News’ Middle East bureau located in Beirut, Lebanon, and he had been looking forward to a fresh assignment - if even just for two to three weeks. In response, Roone assigned Peter Jennings to report the traditional “cultural pieces,” akin to ABC Sports’ famous “Up Close and Personal” segments about Olympic athletes. When he approached the temporary job in Bavaria (which he expected to be more fun than anything else), Peter Jennings had no idea it would be one of the best decisions, yet most difficult events, of his life. More important, he — indeed we — learned some wonderful lessons.

Early in the two weeks before the XX Games began on August 26, 1972, I was moved from an ABC Sports work assignment as a pure, 20-year-old “Go-For” (meaning go for this, go for that…and that I painted doors and swept floors in the broadcast center), to that of a production assistant for Peter Jennings (because Jennings needed someone who could speak German). In the handful of blissful work days leading up to Sept. 5, 1972 as Peter Jennings’ “right hand man,” I discovered that I was expected to shadow Peter and his film/sound crew of three, helping wherever, and with whatever, I could.

Doing “cultural pieces” with Peter Jennings and our British-based crew meant early morning schedules, where we accompanied Peter Jennings to a motley group of places such as Dachau, the notorious World War II concentration camp; to Munich’s Hoffbrauhaus, then the city’s foremost beer hall; and to an occasional Olympic sporting event, when, with a shortage of “real sports announcers,” production schedules meant Peter’s amazing talents of reporting news were morphed slightly into volleyball or weightlifting coverage.

Indeed, early in September 1972, I found myself alone with the soundman, cameraman, and assistant cameraman (but without Peter), explaining (and apologizing) to the vice mayor of Munich why it was that I had arranged an ad hoc “Up With People” concert, without a permit, in order to make for a more lively set of pictures in the famed city center, the Marienplatz.

Because we had worked late the evening of Sept. 4, 1972, Peter told me to sleep in a bit, which meant I arrived at the ABC Sports production center, called Barnathan’s Bungalow, a bit past 8:30a that next Tuesday morning. The minute I stepped into the complex, it was clear that clouds, indeed storms, were brewing. Fear like I had never seen it was in the eyes of one of the American girl I met. She was Jewish, and had traveled to Israel. Elsewhere, instead of looking for sports events to cover, people were figuring out how to get into the Olympic Village, which is where we were told “guerillas” had taken over the Israeli residences. I had to be one of those seeking entrance to the Village, I quickly discovered, because my boss, Peter Jennings, and a film crew, were already inside covering the storm.

A close friend I lived with at the time had connections to the U.S. Olympic team, allowing me to borrow a U.S. team jogging suit, which I donned and then went immediately to the ABC Sports graphics department. There, a brilliant artist changed my grey and red production credential to the green and black of an athlete’s. Following a brief check in to the studio, where I was advised to carry several walkie-talkies, sandwiches for the crew, and fresh film for their cameras, I was on my way toward the Village gate, hoping to wend my way successfully - and unobserved — past onlookers and German military gate guards.

Yet, wouldn’t you know it, along the way, a radio reporter from Iowa stopped me for an “athlete interview,” for which I apologize today, because to keep my cover, I told a white lie and explained how I was a “weightlifter” (I had just seen that sport earlier on the studio monitor, and it was all I could think of). With somewhat long hair, and a skinny 150 pounds, I still laugh at how ridiculous that was.

On the fourth floor of the building facing the Munich Israeli residence that morning, Sept. 5, 1972, I saw my first, in-person sighting of the infamous terrorist with the white pith helmet. The rest of the day, I kept Peter Jennings and the crews as replenished, ready, and updated as possible. Jennings would work for another 20 hours that day, as we moved from one Village building to the next, trying to follow the hostages and their kidnappers. Later that evening, Peter had me speaking on a walkie-talkie to the main studio, standing beside David Wolper on the deck of his 14th story hotel, as we both overlooked the busses that took the nine hostages and their eight captors to Furstenfeldbruck airport. Two hours later, all of the nine Israelis were slaughtered, and all but three of the Palestinians were shot dead by German snipers.

At Furstenfeldbruck the next morning, I was horrified by the huge pool of blood that encircled one of the helicopters where the Israelis had been shot and bombed. Later, in an effort to help put it all into perspective, I will never forget Peter flawlessly - and I believe without a second take - doing a typical Jennings “on camera” that so brilliantly summarized it all: “It is simply this reporter’s observation, that no act of such evil can ruin what is ultimately a successful experiment in human relations.” Those were the paraphrased words that concluded Peter Jennings’ 30-minute special, the one that we produced the day after the massacre, and that aired in the evening telecast of Wednesday, Sept. 6, 1972.

On the evening of the closing ceremonies, I had the honor of joining Peter Jennings and his future wife, Annie Malouf, at a restaurant. Because Peter knew the Palestinian sects, he was able to partially explain what faction of the Black September group had apparently committed the atrocity. He was able to explain some of their history and some of their motivations. Yet, at the end of that evening, we all still struggled with the same thing we struggle with today, following the massacre of another 12 innocents in Aurora, Colorado: Why? Indeed, unbelievably, 40 years later, I still ask why? What did it really accomplish?

Peter was reminded, and taught me, the career importance of hard work, substantial luck, occasional above-average competence, and how you treat people. Haunted himself by less than a high school education, he repeatedly urged others to go as far as they could with education. Security aimed at keeping the evil out, was yet another elemental course, because although most people are good, there are enough who are not.

My colleague at the time, Sean McManus, has since written about Munich, and pointed out how we, as Americans, probably learned for the first time what terrorism was about, when we watched the implosion of the Munich Summer Olympics on ABC. Indeed, it was the first of so many events Americans would see, that continue to haunt us today, and that struggle for more - and better — answers.

Peter and ABC learned through the Munich crisis that big story reporting was really important. And to be reporting live was the only real way to really do it right. Better still, to tell the truth and to know the real facts — and how to really articulate — is the real magic. Peter later made that his calling card. That helped make Peter Jennings the icon, and maybe the legend, he is today, many years after his death. Yet the one thing Peter Jennings did not learn that summer and fall of ‘72, was how to control his tobacco addiction, which took his life on August 7, 2005.

Post, post-script on the fallible human side: In all-too-typical “mad scientist” fashion, that rascal, Peter Jennings, wrote me a personal check for $100 that evening, after dinner, thanking me for the job I did. Excited, I took it to the bank. I found out weeks later after I thought I had cashed it: My revered “Peter Jennings Check” had bounced!

Mr. Jennings, what a pleasure it was to know you. Indeed, Petros, what a pleasure it was to work with you.

Jimmy Schaeffler is chairman and CSO of Carmel-by-the-Sea-based consultancy The Carmel Group (www.carmelgroup.com).

Multichannel Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

Jimmy Schaeffler is chairman and CSO of The Carmel Group, a nearly three-decades-old west coast-based telecom and entertainment consultancy founded in 1995.