Disrupting The Class

Terry Denson caused a stir in the TV world recently by saying aloud what other cable operators only thought to themselves: that Verizon Communications, the nation’s sixth-largest TV provider, should pay only for what people watch. The telco’s FiOS TV, which disrupted cable operators’ world just over seven years ago when it came on the scene touting all-fiber-optic TV and Internet service, is now aiming squarely at programmers.

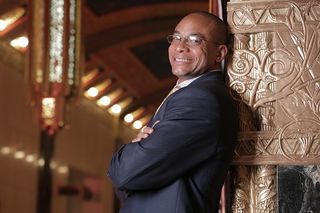

Denson, Verizon’s vice president of content strategy and acquisition, has argued that FiOS should pay a per-subscriber fee to programmers based on a network’s audience, and the telco has the technology to measure that.

He has some allies — even among his sworn enemies — in the fight against programmers who bundle channels in packages to operators. Cablevision recently sued Viacom, charging that the media giant was forcing it to buy channels it didn’t want, instead of allowing it to choose.

Some say it’s a quixotic quest, because big programmers are protected by contracts and the courts. But Denson may be better able to see both sides of the debate. He negotiated contracts for Insight Communications before joining Verizon prior to the launch of FiOS in 2005, and also served as director of business development for the affiliate sales and marketing department of MTV Networks.

He sat down with Multichannel News programming editor R. Thomas Umstead and editor in chief Mark Robichaux to talk about the “Shoe Channel,” the high cost of programming, particularly sports, and why he doesn’t like to play it safe.

MCN: You made some waves a few weeks ago with a statement that you are “paying for a customer who never goes to the channel.” Since you made that statement, have you received a little pushback from some of the networks?

Terry Denson: All of our active discussions involve converting to that viewership-based business model. What I like about the model is that it does three primary things, from my perspective. One of the things that it allows is as a distributor we have to make difficult decisions as to how to allocate our capacity, which includes long-term distribution commitments. We want to make sure that there’s a rational basis for that distribution and for that cost.

Multichannel Newsletter

The smarter way to stay on top of the multichannel video marketplace. Sign up below.

Second, what this does is it actually reduces the risk in that particular commitment if it creates a cost rationalization of committing to an upstart new programmer or a diversified programmer. I’d be willing to make that commitment to provide distribution for that content provider and, in exchange for that, I know that if the customers value that content, that I am paying rational against that. But if they don’t value it, I am not stuck with additional content costs that aren’t being rationalized by customer consumption.

I think that that’s a key component, in that it actually encourages distributors to take a chance on independents or emerging programmers, because the risk is lower. It creates cost rationalization for a distributor, which I think then results in stabilized pricing.

The third thing it does, which I think is also compelling, is that it encourages the big programmers — the conglomerates, if you will — to invest in programming across all of their channels … to the extent that there is a content provider that has a suite of channels and some of those channels are more popular and some are more widely distributed and some are less popular, less widely distributed.

MCN: How are content producers reacting?

TD: In this particular model, if you’re going to sign up to carry this suite of channels, it encourages the content provider to invest accordingly in those lesser-viewed suites of channels, because if they don’t, then they won’t get the viewership. And if they do, not only do they get the viewership, then they get the double benefit of being paid more and, if their viewership is higher, then they are going to have more advertising that comes along with it.

So all it does is encourages content providers. It doesn’t allow any garden to go untended, and the active garden approach I think is healthy for everyone. I think essentially what that does is that eliminates, or at least reduces, these “carriage by PowerPoint” type of deals.

And I’m sure you can have a fancy sizzle reel, but carriage by PowerPoint, someone comes up with this big deck and they show all these statistics about how everyone wears shoes, the average American has 9.7 pairs of shoes in their closet and spends over $500 on shoes, whatever it is, therefore we should have the Shoe Channel. Wouldn’t everybody watch the Shoe Channel? Everyone has them.

The notion of investing in a rights position — sports, movies and otherwise —and turning around and then trying to mitigate that investment or monetize that investment directly against the subscription fee, that is where we historically have been and it cannot be where we will end up.

MCN: What do you mean?

TD: It sooner or later becomes an unsustainable model. I don’t know what that tipping point is. As we look at the emerging business models out in the marketplace, there is a significant position in direct-to-consumer. Obviously, over-the-top is a growing area. All of that is going to have an impact of having some influence on the traditional licensee-licensor model between content provider and distributor.

MCN: What’s your time frame?

TD: It’s all active now, active negotiations. It’s the model that we’re converting to. In all candor, are we going to get there with everyone in the next 12 months? I’d like to, but I can’t say that we will. It’s our position is we’re converting to a viewership-based payment model.

MCN: A lot of operators silently applauded you when you did this. But on the other side, what do you say to the smaller, independent programmers who maybe feel disenfranchised because of this?

TD: This is great for the smaller programmers, the smaller and midsized programmers. It’s perfect for them because those are the programmers that are the most vulnerable. They’ve been marginalized on a tier. They have difficulty winning distribution. I mean you’ve seen the lawsuits.

If the programmer does what they believe they can do and they invest in the programming, and they market it effectively, and customers like it, then I am more than happy to pay for that for all those customers who are engaging. And that’s the cost rationalization.

MCN: And how will you decide, OK, you’re worthy?

TD: We will still evaluate from an editorial perspective. And we’ll still apply similar rigor as we have in the past. I think it’s really more about the business model and the distribution opportunity for an emerging programmer. This doesn’t mean that the doors are open and anyone can sign up and get capacity on the network. You still have to go out and prove your case.

MCN: How do you determine the viewership?

TD: Not Nielsen. I think with advances in the accuracy of set-top box data — I know ours is extremely accurate — and our ability to generate real-time reports against that, we can literally identify measurement down to the household, down to the unique household, down to the minute. And that enables this kind of model.

MCN: Will this catch on with other operators?

TD: You’re never going to get everybody into the fold at one time. I think it’s really about establishing the precedent. If it works for people, then I wouldn’t be surprised if it were adopted as an industry norm.

MCN: Why hasn’t there been more progress on TV Everywhere?

TD: There’s definitely a usage gap. I’d cite two reasons specifically. One is it’s not easy — it’s not easy to access. And two, there is no ubiquity or uniformity of experience. So you take those two things and customers, [and] it creates a high barrier for usage.

From my perspective, anyway, the authentication process is not consistent with the behavioral practices that consumers already have, now which is fine if it’s better and easier, right? That’s what Steve Jobs did for us, OK? He said the behavior is here. I’ll make it better and easier for you.

We as an industry have made it clunkier and inconsistent, so I think that’s part of the issue. And, so, how do you change that? I think the answer probably was technology.

MCN: What about VOD, which has a lot of new competition?

TD: I think you can’t play it so safe. And I haven’t seen a situation in our industry where taking a conservative position has resulted in a dramatic shift in human behavior and consumption patterns and, I think, in business growth.

On video-on-demand, several content providers were conservative, concerned about cannibalization. The two things that I heard most, going way back now: One, I’m concerned about cannibalization; and two, I can’t figure out how to monetize, so therefore I won’t do it.

So, the dramatic shift in video-on-demand occurred. I can cite two or three key examples, but the primary dramatic shift in video-on-demand occurred when there was a significant push for free content, free on-demand. What free on-demand did was it effectively allowed more customers to sample and as more customers sampled, then that accelerated adoption.

Another key element was the inclusion of premium SVOD services with the actual premium package itself. Customers could then again consume content that they want to consume anyway and that also accelerated the adoption of video-on-demand. So those two key components were real helpful.

MCN: What are you doing to bring down sports fees?

TD: One of the concerns that I have as a distributor is that the cost of sports is really infiltrating and pervading through more mainstream channels. What that does is that actually puts pressure on those individual channels and then, in turn, puts pressure on us at the negotiating table with retransmission-consent fees now being something that just about every operator has to contemplate.

If a broadcaster invests in sports rights, then they’re going to look to defray those costs or monetize those costs through fees. In cable, general-entertainment services want to increase their position in sports, then they look to monetize it or mitigate that position in the negotiation.

Think about just three or four points in time … first, sports were on broadcast television in one particular area. You could even expand that to ESPN. You could identify where sports reside and have rational conversations around that and rational expectations.

Then there was the advent of regional sports networks, and then single-team regional sports networks. Now, those rights then get diversified among two or three regional sports networks, each of which is asking for a fee that’s higher than almost any fee — then that’s hard. And these are all sort of body punches, if you will, for a distributor, you know?

I think if you looked at your channel lineup today, among the top 60 to 80 channels, there’s a significant number of those channels that have invested in sports rights, and some are in deeper positions — so as Turner gets deeper into sports, as Fox diversifies more into sports.

MCN: You were one of the first companies to put a surcharge on sports of $2.42. Is that the answer, charge more for sports tiers?

TD: I’m not sure I would call that the answer. We certainly don’t want to put more cost pressure on the consumer, No. 1. But I do think our select HD offering, which effectively is a sports-free offering, provides economic value to a customer who is looking for that. I think that’s helpful.

There are certainly plenty of people out there who just aren’t interested in sports. We have a content offering that addresses that customer base and we’ll see how that resonates.

But in terms of a macro solution, I don’t have one. I’d love to hear anyone who does.

MCN: What are you most excited about at FiOS right now?

TD: I think our position with FiOS Quantum is exciting. It’s one of those positions of innovation where we have identified customer aspiration and we will be waiting for them when they get there.

And maybe you don’t need 75 [Megabits per second] but we anticipate that there is a period where you’ll either want it or need it and even more, 300 Mbps, whatever the case may be.

We are certainly looking to make sure that our innovation meets or outpaces customer aspiration, so customers basically arrive to a place that’s ready for them like we knew they were coming.

MCN: How much broadband is enough?

TD: I don’t know, but I think if you take this variable concept of innovation that is ahead of customer aspiration, you’re gonna be OK. With our plans and our architecture in fiber we’re going to be in a [good] position.

MCN: Where do you see the future of TV moving?

TD: From a customer perspective, I think it’s an exciting time with Smart TV and IP-connected devices. And I think it was a great opportunity to access diverse content either directly or with the assistance of a forward thinking middle entity.

I would say that that’s where I would see the first big change. Thereafter, the television device, I think, continues to be important.

MCN: How’s the cable competition, particularly on Long Island?

TD: We knew we were going to face fierce competition with the entry of the product and I think we’ve done a terrific job of executing against that. The competition has been good for the consumer; it’s been good for us.

MCN: FiOS had many doubters seven years ago. Do you feel vindicated?

TD: There are two things that I don’t look for in this business or this job, one is vindication and two is validation. If you’re seeking that, then it can be a little bit challenging. We do what we believe is the right thing to do at the right time. We execute against it.

And we’ve been, I think, real forthcoming in publishing what we want to accomplish. I think someone else can decide whether we’ve done it and whether we’re doing a good job of it. I can only try my best.